Bank Robber presents the official NEGRO LEAGUES thread

- Thread starter Butt Rubber

- Start date

Josh Gibson

No joshing about Gibson's talents

By Larry Schwartz

Special to ESPN.com

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Often it is difficult to distinguish fact from fiction -- especially regarding statistics -- when it comes to players of the Negro League. But there is no disputing the accomplishments of Josh Gibson, whose batting feats are legendary.

Before dying at age 35, three months before Jackie Robinson's major-league debut, Josh Gibson had proven to Negro League followers that he was one of the game's greats.

Voted into the Hall of Fame in 1972 by the Committee on Negro Baseball Leagues, the right-handed hitting catcher never received the opportunity to show his stuff in the major leagues because he was an African-American. He died at the age of 35 in early 1947, three months before Jackie Robinson made his historic major-league debut with the Brooklyn Dodgers.

Gibson is often referred to as the black Babe Ruth for his ability to hit tape-measure homers, and he also hit for incredibly high averages.

"He hits the ball a mile," Hall of Famer Walter Johnson, the Washington Senators pitcher who won 416 games, said of Gibson.

Satchel Paige, who was Gibson's teammate on the Pittsburgh Crawfords and later pitched for the Cleveland Indians, said, "He was the greatest hitter who ever lived."

In various publications, the 6-foot-1, 215-pounder has been credited with as many as 84 homers in one season. His Hall of Fame plaque says he hit "almost 800" homers in his 17-year career. His lifetime batting average was higher than .350, with one book putting it at .384, best in Negro League history.

It was reported that he won nine home-run titles and four batting championships playing for the Crawfords and the Homestead Grays. In two seasons in the late 1930s, it was written that not only did he hit higher than .400, but his slugging percentage was above 1.000.

Belting home runs of more than 500 feet was not unusual for Gibson. One homer in Monessen, Pa., reportedly was measured at 575 feet. The Sporting News of June 3, 1967 credits Gibson with a home run in a Negro League game at Yankee Stadium that struck two feet from the top of the wall circling the center field bleachers, about 580 feet from home plate. Although it has never been conclusively proven, Chicago American Giants infielder Jack Marshall said Gibson slugged one over the third deck next to the left field bullpen in 1934 for the only fair ball hit out of the House That Ruth Built.

Gibson was born Dec. 21, 1911 in Buena Vista, Ga., and his family reportedly moved to Pittsburgh in the 1920s. By the time he was a teenager, Gibson was playing semipro baseball. His professional career began at the age of 18 under unusual circumstances.

With the Grays and Kansas City Monarchs playing a night game under a portable lighting system in Pittsburgh in 1930, the Grays catcher suffered an injury to his hand, according to the book "The Ballplayers." Homestead manager Judy Johnson, who knew of Gibson's reputation as a terrific semipro player, went into the stands looking for the 18-year-old.

"I asked him if he wanted to catch and he said 'yes, sir,' so we had to hold up the game while he went and put on Buck Ewing's uniform," Johnson said. "We signed him the next day."

Gibson played for the Grays the rest of that season and 1931, before jumping to the Crawfords and winning three home-run titles in five seasons. He caught Paige in 1936 to form the most popular battery in African-American history. After starting 1937 in the Dominican Republic, he returned in the summer to play for the Grays.

He won two more home-run titles, in 1938 and 1939, as well as a batting championship in 1938. There are stories that the Senators and Pittsburgh Pirates considered giving the powerful catcher a tryout in the late '30s, but because of the color of his skin he was never granted the opportunity.

In 1940 and 1941, he chose to play south of the border, undoubtedly because of greater financial rewards. After starring for Vera Cruz of the Mexican League, he played in the Puerto Rican Winter League, earning Most Valuable Player honors and a batting title. Gibson was forced to abandon the Mexican League and return to the Grays in 1942 after the team's owner, Cum Posey, hit him with a lawsuit. Gibson led the Negro League in hitting and home runs.

Early the next year, Gibson suffered a brain tumor that put him in a coma. When he awoke, doctors wanted to operate. But Gibson wouldn't let them, fearing that surgery would leave him a vegetable. Despite recurring headaches and a drinking problem, he continued to tear apart the Negro League, winning two more batting crowns and three more home-run titles in the next four seasons.

Although he was mediocre defensively early in his career, he improved through the years. Teammate Cool Papa Bell, who also was voted into the Hall of Fame, said Gibson was a good catcher, had a strong arm and was a good handler of pitchers but had difficulty on pop fouls.

"The Ballplayers" recites this story of the black Babe Ruth's last day: "On Jan. 20, 1947, Gibson told his mother that he was going to die that night. She laughed, but told him to go to bed and that she would call a doctor. With his family gathered around him, Gibson asked for his baseball trophies to be brought to his bedside. He was laughing and talking when he suddenly sat straight up, had a stroke and died."

Dr Bank Robbers analysis:

Alot about Gibson's life is myth. Gibson wasn't "picked out of the crowd" to make his first start when Buck Ewing injured his finger, he was actually signed as a backup the day before by the Grays (from the semipro Crawfords).

As for his death, the story about him gathering his trophies is fake. In reality he went into a coma and died by himself.

Still an interesting article, none the less

No joshing about Gibson's talents

By Larry Schwartz

Special to ESPN.com

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Often it is difficult to distinguish fact from fiction -- especially regarding statistics -- when it comes to players of the Negro League. But there is no disputing the accomplishments of Josh Gibson, whose batting feats are legendary.

Before dying at age 35, three months before Jackie Robinson's major-league debut, Josh Gibson had proven to Negro League followers that he was one of the game's greats.

Voted into the Hall of Fame in 1972 by the Committee on Negro Baseball Leagues, the right-handed hitting catcher never received the opportunity to show his stuff in the major leagues because he was an African-American. He died at the age of 35 in early 1947, three months before Jackie Robinson made his historic major-league debut with the Brooklyn Dodgers.

Gibson is often referred to as the black Babe Ruth for his ability to hit tape-measure homers, and he also hit for incredibly high averages.

"He hits the ball a mile," Hall of Famer Walter Johnson, the Washington Senators pitcher who won 416 games, said of Gibson.

Satchel Paige, who was Gibson's teammate on the Pittsburgh Crawfords and later pitched for the Cleveland Indians, said, "He was the greatest hitter who ever lived."

In various publications, the 6-foot-1, 215-pounder has been credited with as many as 84 homers in one season. His Hall of Fame plaque says he hit "almost 800" homers in his 17-year career. His lifetime batting average was higher than .350, with one book putting it at .384, best in Negro League history.

It was reported that he won nine home-run titles and four batting championships playing for the Crawfords and the Homestead Grays. In two seasons in the late 1930s, it was written that not only did he hit higher than .400, but his slugging percentage was above 1.000.

Belting home runs of more than 500 feet was not unusual for Gibson. One homer in Monessen, Pa., reportedly was measured at 575 feet. The Sporting News of June 3, 1967 credits Gibson with a home run in a Negro League game at Yankee Stadium that struck two feet from the top of the wall circling the center field bleachers, about 580 feet from home plate. Although it has never been conclusively proven, Chicago American Giants infielder Jack Marshall said Gibson slugged one over the third deck next to the left field bullpen in 1934 for the only fair ball hit out of the House That Ruth Built.

Gibson was born Dec. 21, 1911 in Buena Vista, Ga., and his family reportedly moved to Pittsburgh in the 1920s. By the time he was a teenager, Gibson was playing semipro baseball. His professional career began at the age of 18 under unusual circumstances.

With the Grays and Kansas City Monarchs playing a night game under a portable lighting system in Pittsburgh in 1930, the Grays catcher suffered an injury to his hand, according to the book "The Ballplayers." Homestead manager Judy Johnson, who knew of Gibson's reputation as a terrific semipro player, went into the stands looking for the 18-year-old.

"I asked him if he wanted to catch and he said 'yes, sir,' so we had to hold up the game while he went and put on Buck Ewing's uniform," Johnson said. "We signed him the next day."

Gibson played for the Grays the rest of that season and 1931, before jumping to the Crawfords and winning three home-run titles in five seasons. He caught Paige in 1936 to form the most popular battery in African-American history. After starting 1937 in the Dominican Republic, he returned in the summer to play for the Grays.

He won two more home-run titles, in 1938 and 1939, as well as a batting championship in 1938. There are stories that the Senators and Pittsburgh Pirates considered giving the powerful catcher a tryout in the late '30s, but because of the color of his skin he was never granted the opportunity.

In 1940 and 1941, he chose to play south of the border, undoubtedly because of greater financial rewards. After starring for Vera Cruz of the Mexican League, he played in the Puerto Rican Winter League, earning Most Valuable Player honors and a batting title. Gibson was forced to abandon the Mexican League and return to the Grays in 1942 after the team's owner, Cum Posey, hit him with a lawsuit. Gibson led the Negro League in hitting and home runs.

Early the next year, Gibson suffered a brain tumor that put him in a coma. When he awoke, doctors wanted to operate. But Gibson wouldn't let them, fearing that surgery would leave him a vegetable. Despite recurring headaches and a drinking problem, he continued to tear apart the Negro League, winning two more batting crowns and three more home-run titles in the next four seasons.

Although he was mediocre defensively early in his career, he improved through the years. Teammate Cool Papa Bell, who also was voted into the Hall of Fame, said Gibson was a good catcher, had a strong arm and was a good handler of pitchers but had difficulty on pop fouls.

"The Ballplayers" recites this story of the black Babe Ruth's last day: "On Jan. 20, 1947, Gibson told his mother that he was going to die that night. She laughed, but told him to go to bed and that she would call a doctor. With his family gathered around him, Gibson asked for his baseball trophies to be brought to his bedside. He was laughing and talking when he suddenly sat straight up, had a stroke and died."

Dr Bank Robbers analysis:

Alot about Gibson's life is myth. Gibson wasn't "picked out of the crowd" to make his first start when Buck Ewing injured his finger, he was actually signed as a backup the day before by the Grays (from the semipro Crawfords).

As for his death, the story about him gathering his trophies is fake. In reality he went into a coma and died by himself.

Still an interesting article, none the less

CHINO SMITH

South Carolina native made a name for himself

as one of Negro League's top all-time hitters

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

By DEAN LOLLIS

GREENWOOD, S.C. -- He is considered to be one of the greatest hitters ever in baseball. He was listed in Sports Illustrated's Top 50 Athletes from South Carolina. Yet, the legacy of Chino Smith remains a mystery to many -- even those in his hometown.

Smith was born in Greenwood, South Carolina, in 1903. By the time he died in 1931, Smith was considered to be among the greatest players to ever take the field in the Negro Leagues.

In just six seasons, Smith is credited with a career batting average of no less than .428. He was also the first Negro League player to hit a home run in Yankee Stadium.

Getting his start

Smith's baseball career probably started when he played for Benedict College. In the summer, he found a job carrying bags at New York's Pennsylvania Station. After work, he would join other black youth with baseball dreams as a member of the Pennsylvania Redcaps. The Redcaps appear to have been the

equivalent of a semi-pro team.

In 1924, Smith joined the Pennsylvania Redcaps, another semi-pro team. A year later, he became a player for the Brooklyn Royal Giants, a member of the the Eastern Colored League. Smith debuted at second base and hit a robust .341 in his first season.

In the next few years of his career, his style of play would draw comparisons to Lloyd Waner, a member of the Pittsburgh Pirates and a future member of the Hall of Fame. Smith's style of play was also compared to a later player, Rod Carew.

Skill and swagger

Smith, just 5-foot-6, quickly earned a reputation as a hitter -- and a fighter. In a publication from the Society of American Baseball Research, Bill Holland, a top Negro Leagues pitcher in the 1920s, recalls Smith as one who openly sought disapproval from the crowd.

"This guy could do more with the fans down on him," Holland said. "He'd get up to bat and the pitcher would throw one in there and he'd spit at it.

"The fans would boo him, and he'd come out of the batter's box, turn around and make like he was going to move toward hem, and they'd shout, 'Come On!' He'd get back in there and hit the ball out of the ball park and go around the bases waving his arms at the stands."

He played with the Royal Giants from 1925-1928. In 1927, he finished second in the league with a .439 batting average. According to reports, Smith rarely struck out.

In 1929,. he joined the Lincoln Giants and promptly established himself as one of the league's top players. His .464 average led the league. He added 23 home runs in 237 at-bats -- also enough to lead the league. His most astounding feat, however, was a slugging percentage of .930.

'He could do everything'

Hall of Famer Cool Papa Bell is quoted in the SABR publication as saying Smith would "go out there, say 'I guess I'll get me three hits,' and go out there and hit that ball. I don't care who pitched, he could do everything."

One of Smith's biggest accomplishments came on July 5, 1930. The Lincoln Giants faced the Brooklyn Black Sox in the first game between Negro League teams at Yankee Stadium. Smith responded by becoming the first Negro Leaguer to hit a home run in the "House that Ruth Built." He added a triple and another home run in that game, driving in six runs.

Smith had the honor of playing in the same spot that Babe Ruth played during New York home games. He also bat in the same spot in the order -- third -- as the Great Bambino. The Giants continued to use Yankee Stadium when the New York Yankees were on road trips.

Offense was the only thing that got Smith noticed. He earned a reputation as a fielder. According to stories, Smith had a knack for quickly throw the ball to first and catching unsuspecting base runners off guard.

"Chino Smith was out there, and he could field a ball, and if you made a wide turn at first base, he could throw you out trying to hustle back," recalled Giants teammate Bill Yancey.

Following the 1930 season, the Lincoln Giants challenged the Homestead Grays to a championship series. In the 10th and final game of that series, Smith collided with a teammate while chasing down a pop fly. Smith was hit with a knee in the stomach and had to be removed from the field.

A career cut short

It was the last time he would ever play in the United States. He took just a few at-bats that winter in Cuba. Some feel the injury led to Smith coming down with yellow fever. By the time the 1931 season started, Smith had fallen victim to the disease.

Smith's accomplishments in his short career weren't confined to Negro League competition. In games against Major League teams, Smith collected 22 hits in 48 at-bats for a .458 average. In 1926, Smith faced Major League pitching for the first time and hit a single and a home run off New York's Roy Sherid.

Smith only played six seasons in the Negro Leagues, but many consider him to have been one of its greatest stars. In "Only the Ball was White" by Robert Pearson, legendary pitcher Satchell Paige labels Smith as one of the two greatest hitters ever in the Negro Leagues.

Dr Bank Robbers analysis:

According to the Baltimore Afro-American, Smith's 1927 stats were:

G-34

AB-114

H-50

R-26

Ave-.439

1928 stats

1928 Brooklyn Royal Giants (played 2B)

Gm-9

AB-36

H-13

Do-2

Tr-2

HR-1

R-9

BB-0

HBP-1

Ave-.361

OBP-.378

SLG-.611

South Carolina native made a name for himself

as one of Negro League's top all-time hitters

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

By DEAN LOLLIS

GREENWOOD, S.C. -- He is considered to be one of the greatest hitters ever in baseball. He was listed in Sports Illustrated's Top 50 Athletes from South Carolina. Yet, the legacy of Chino Smith remains a mystery to many -- even those in his hometown.

Smith was born in Greenwood, South Carolina, in 1903. By the time he died in 1931, Smith was considered to be among the greatest players to ever take the field in the Negro Leagues.

In just six seasons, Smith is credited with a career batting average of no less than .428. He was also the first Negro League player to hit a home run in Yankee Stadium.

Getting his start

Smith's baseball career probably started when he played for Benedict College. In the summer, he found a job carrying bags at New York's Pennsylvania Station. After work, he would join other black youth with baseball dreams as a member of the Pennsylvania Redcaps. The Redcaps appear to have been the

equivalent of a semi-pro team.

In 1924, Smith joined the Pennsylvania Redcaps, another semi-pro team. A year later, he became a player for the Brooklyn Royal Giants, a member of the the Eastern Colored League. Smith debuted at second base and hit a robust .341 in his first season.

In the next few years of his career, his style of play would draw comparisons to Lloyd Waner, a member of the Pittsburgh Pirates and a future member of the Hall of Fame. Smith's style of play was also compared to a later player, Rod Carew.

Skill and swagger

Smith, just 5-foot-6, quickly earned a reputation as a hitter -- and a fighter. In a publication from the Society of American Baseball Research, Bill Holland, a top Negro Leagues pitcher in the 1920s, recalls Smith as one who openly sought disapproval from the crowd.

"This guy could do more with the fans down on him," Holland said. "He'd get up to bat and the pitcher would throw one in there and he'd spit at it.

"The fans would boo him, and he'd come out of the batter's box, turn around and make like he was going to move toward hem, and they'd shout, 'Come On!' He'd get back in there and hit the ball out of the ball park and go around the bases waving his arms at the stands."

He played with the Royal Giants from 1925-1928. In 1927, he finished second in the league with a .439 batting average. According to reports, Smith rarely struck out.

In 1929,. he joined the Lincoln Giants and promptly established himself as one of the league's top players. His .464 average led the league. He added 23 home runs in 237 at-bats -- also enough to lead the league. His most astounding feat, however, was a slugging percentage of .930.

'He could do everything'

Hall of Famer Cool Papa Bell is quoted in the SABR publication as saying Smith would "go out there, say 'I guess I'll get me three hits,' and go out there and hit that ball. I don't care who pitched, he could do everything."

One of Smith's biggest accomplishments came on July 5, 1930. The Lincoln Giants faced the Brooklyn Black Sox in the first game between Negro League teams at Yankee Stadium. Smith responded by becoming the first Negro Leaguer to hit a home run in the "House that Ruth Built." He added a triple and another home run in that game, driving in six runs.

Smith had the honor of playing in the same spot that Babe Ruth played during New York home games. He also bat in the same spot in the order -- third -- as the Great Bambino. The Giants continued to use Yankee Stadium when the New York Yankees were on road trips.

Offense was the only thing that got Smith noticed. He earned a reputation as a fielder. According to stories, Smith had a knack for quickly throw the ball to first and catching unsuspecting base runners off guard.

"Chino Smith was out there, and he could field a ball, and if you made a wide turn at first base, he could throw you out trying to hustle back," recalled Giants teammate Bill Yancey.

Following the 1930 season, the Lincoln Giants challenged the Homestead Grays to a championship series. In the 10th and final game of that series, Smith collided with a teammate while chasing down a pop fly. Smith was hit with a knee in the stomach and had to be removed from the field.

A career cut short

It was the last time he would ever play in the United States. He took just a few at-bats that winter in Cuba. Some feel the injury led to Smith coming down with yellow fever. By the time the 1931 season started, Smith had fallen victim to the disease.

Smith's accomplishments in his short career weren't confined to Negro League competition. In games against Major League teams, Smith collected 22 hits in 48 at-bats for a .458 average. In 1926, Smith faced Major League pitching for the first time and hit a single and a home run off New York's Roy Sherid.

Smith only played six seasons in the Negro Leagues, but many consider him to have been one of its greatest stars. In "Only the Ball was White" by Robert Pearson, legendary pitcher Satchell Paige labels Smith as one of the two greatest hitters ever in the Negro Leagues.

Dr Bank Robbers analysis:

According to the Baltimore Afro-American, Smith's 1927 stats were:

G-34

AB-114

H-50

R-26

Ave-.439

1928 stats

1928 Brooklyn Royal Giants (played 2B)

Gm-9

AB-36

H-13

Do-2

Tr-2

HR-1

R-9

BB-0

HBP-1

Ave-.361

OBP-.378

SLG-.611

Oscar Charleston

Considered by many the greatest Negro League player of all, multi-talented Oscar Charleston was often compared with three great white contemporaries: his hitting and speedy, aggressive baserunning (and hard-sliding style) brought favorable comparison to Ty Cobb; his physique (he was barrel-chested, with spindly legs), power, and popularity, particularly with youngsters, were reminiscent of Babe Ruth; and his defensive style and skills, playing a shallow, far-ranging centerfield with a strong, accurate arm and excellent fly ball judgment, brought visions of Tris Speaker. The New York Giants' John McGraw, familiar with the untapped black talent available, considered the 6' 190-lb Charleston the best, and coveted him.

A native of Indianapolis, Charleston grew up serving as batboy for the local ABC's. At age 15, he joined the army and was stationed in the Philippines. The military gave the underage runaway the opportunity to display his abilities in track and baseball; he ran the 220-yard dash in 23 seconds, and played in the otherwise all-white Manila League. Entering big-time black baseball with the ABC's, he was a vital cog in their 1916 Black World Series triumph over the Chicago American Giants, batting .360 in seven of the 10 games played. After stints with the American Giants and New York Lincoln Stars, he rejoined Indianapolis when the Negro National League was organized in 1920.

Through 1923, the lefthanded-hitting and throwing Charleston posted a .370 batting average with the NNL ABC's and St. Louis Giants, and in 1921 led the league in hitting (.446), triples (10), HR (14), total bases (137), slugging (.774), and stolen bases (28), finishing second with 79 hits in 50 games. From 1922 to 1925, he was player-manager for the Eastern Colored League Harrisburg Giants, and, after a second-division finish in 1924, he led them to three consecutive second-place finishes. In 1925, he batted .424. From 1928 to 1931, he hit .347 in two-year stints with the Hilldale club and the Homestead Grays. The Grays won a 10-game Eastern Championship Series from the New York Lincoln Giants in 1930.

In 1932 Gus Greenlee persuaded Charleston to manage his Pittsburgh Crawfords. Josh Gibson, Judy Johnson, and Satchel Paige joined him to give the club four future Hall of Famers. Operating independently, they went 99-36 as their 36-year-old manager batted .363, second on the club to Gibson. Often considered black baseball's greatest team, the Crawfords became the dominant member of the tough National Negro Association, which operated from 1933 to 1936. Pittsburgh claimed the 1933 pennant, as did the Chicago American Giants, without resolution. In 1935 the Crawfords won the first NNL's only undisputed title. In 1936 they posted the best overall record, winning the second half of the split season. A title series with the first-half champion Washington Elite Giants was never completed, though the Giants won the only game played, 2-0.

Charleston remained with the Crawfords through 1940, following them in moves to Toledo and Indianapolis. He became manager of the NNL Philadelphia Stars in 1941 and the Brooklyn Brown Dodgers when Branch Rickey formed the United States League in 1945. He was thus put in a position to scout and evaluate players for organized baseball's integration. He managed through 1954, leading the Indianapolis Clowns to the '54 Negro American League title, but died after the season.

Statistics so far compiled show that Charleston batted .353 lifetime. He twice led the Cuban Winter League in SB, and had 31 during the 1923-24 campaign, setting a record that stood for more than 20 years. In 53 exhibition games against white major leaguers, he hit .318 with 11 HR.

Charleston had a famous temper, and enjoyed brawling, resulting in legendary encounters with umpires, opponents, agents raiding his teams, a Ku Klux Klansman, and, on one occasion, several Cuban soldiers. As his legs gave out, he moved from centerfield to first base, yet as long as he played, he never lost his home run power, nor his meanness on the basepaths. He was sympathetic toward young players, and was protective of rookie teammates. A demanding manager who expected his players to perform as well as he did, his strength as a pilot lay in his understanding of the intricacies of the game. He was elected to the Hall of Fame by the Committee on Negro Baseball Leagues in 1976. (MFK)

Dr Bank Robbers analysis:

While I'm sure the "Cobb-Ruth-Speaker rolled into one" description is exagerated, Charleston in the negro leagues was a man among boys.

Of the numbers that do exist on Charleston, he hit .357 in 821 games, with 151 HR's, 63 triples, and 184 doubles, a SLG% of .579.

For the games where records exist, in 1925 Oscar hit .445 in 68 games, with 21 doubles and 20 HR's.

Considered by many the greatest Negro League player of all, multi-talented Oscar Charleston was often compared with three great white contemporaries: his hitting and speedy, aggressive baserunning (and hard-sliding style) brought favorable comparison to Ty Cobb; his physique (he was barrel-chested, with spindly legs), power, and popularity, particularly with youngsters, were reminiscent of Babe Ruth; and his defensive style and skills, playing a shallow, far-ranging centerfield with a strong, accurate arm and excellent fly ball judgment, brought visions of Tris Speaker. The New York Giants' John McGraw, familiar with the untapped black talent available, considered the 6' 190-lb Charleston the best, and coveted him.

A native of Indianapolis, Charleston grew up serving as batboy for the local ABC's. At age 15, he joined the army and was stationed in the Philippines. The military gave the underage runaway the opportunity to display his abilities in track and baseball; he ran the 220-yard dash in 23 seconds, and played in the otherwise all-white Manila League. Entering big-time black baseball with the ABC's, he was a vital cog in their 1916 Black World Series triumph over the Chicago American Giants, batting .360 in seven of the 10 games played. After stints with the American Giants and New York Lincoln Stars, he rejoined Indianapolis when the Negro National League was organized in 1920.

Through 1923, the lefthanded-hitting and throwing Charleston posted a .370 batting average with the NNL ABC's and St. Louis Giants, and in 1921 led the league in hitting (.446), triples (10), HR (14), total bases (137), slugging (.774), and stolen bases (28), finishing second with 79 hits in 50 games. From 1922 to 1925, he was player-manager for the Eastern Colored League Harrisburg Giants, and, after a second-division finish in 1924, he led them to three consecutive second-place finishes. In 1925, he batted .424. From 1928 to 1931, he hit .347 in two-year stints with the Hilldale club and the Homestead Grays. The Grays won a 10-game Eastern Championship Series from the New York Lincoln Giants in 1930.

In 1932 Gus Greenlee persuaded Charleston to manage his Pittsburgh Crawfords. Josh Gibson, Judy Johnson, and Satchel Paige joined him to give the club four future Hall of Famers. Operating independently, they went 99-36 as their 36-year-old manager batted .363, second on the club to Gibson. Often considered black baseball's greatest team, the Crawfords became the dominant member of the tough National Negro Association, which operated from 1933 to 1936. Pittsburgh claimed the 1933 pennant, as did the Chicago American Giants, without resolution. In 1935 the Crawfords won the first NNL's only undisputed title. In 1936 they posted the best overall record, winning the second half of the split season. A title series with the first-half champion Washington Elite Giants was never completed, though the Giants won the only game played, 2-0.

Charleston remained with the Crawfords through 1940, following them in moves to Toledo and Indianapolis. He became manager of the NNL Philadelphia Stars in 1941 and the Brooklyn Brown Dodgers when Branch Rickey formed the United States League in 1945. He was thus put in a position to scout and evaluate players for organized baseball's integration. He managed through 1954, leading the Indianapolis Clowns to the '54 Negro American League title, but died after the season.

Statistics so far compiled show that Charleston batted .353 lifetime. He twice led the Cuban Winter League in SB, and had 31 during the 1923-24 campaign, setting a record that stood for more than 20 years. In 53 exhibition games against white major leaguers, he hit .318 with 11 HR.

Charleston had a famous temper, and enjoyed brawling, resulting in legendary encounters with umpires, opponents, agents raiding his teams, a Ku Klux Klansman, and, on one occasion, several Cuban soldiers. As his legs gave out, he moved from centerfield to first base, yet as long as he played, he never lost his home run power, nor his meanness on the basepaths. He was sympathetic toward young players, and was protective of rookie teammates. A demanding manager who expected his players to perform as well as he did, his strength as a pilot lay in his understanding of the intricacies of the game. He was elected to the Hall of Fame by the Committee on Negro Baseball Leagues in 1976. (MFK)

Dr Bank Robbers analysis:

While I'm sure the "Cobb-Ruth-Speaker rolled into one" description is exagerated, Charleston in the negro leagues was a man among boys.

Of the numbers that do exist on Charleston, he hit .357 in 821 games, with 151 HR's, 63 triples, and 184 doubles, a SLG% of .579.

For the games where records exist, in 1925 Oscar hit .445 in 68 games, with 21 doubles and 20 HR's.

A shortstop, Lloyd was often referred to as the "Black Wagner." The great Honus Wagner commented on the nickname, "I am honored to have John Lloyd called the Black Wagner. It's a privilege to have been compared to him." Like Wagner, the 5-foot-11, 180-pound Lloyd had long arms, big hands, great speed for his size, and great lateral range. Unlike Wagner, he batted left-handed.

Although he was a soft-spoken, easy-going man who genuinely loved baseball, Lloyd was also a fierce competitor on the field and he was continually moving from one team to another to get a raise. "Wherever the money was, that's where I was," he once said.

Lloyd played second base in his first professional season with the Cuban X Giants in 1906, but was moved to shortstop when he joined the Philadelphia Giants the following year. After three seasons there, he went to the Chicago Leland Giants with several teammates and the Philadelphia team folded.

During the winters, Lloyd usually played in Cuba, where he was known as "El Cucharo" (the Shovel) because he often came up with pebbles and pieces of the infield dirt when he scooped up a grounder.

In 1910, his Cuban team played a 12-game exhibition series against the Detroit Tigers, led by Ty Cobb. Lloyd hit .500 to Cobb's .370.

Lloyd went to the Lincoln Giants in New York in 1911, and he moved back to Chicago, with the American Giants, in 1913. He stayed there through the 1917 season, then became player manager of the Brooklyn Royal Giants in 1918.

From that time on, Lloyd began to play first base more often than shortstop. He played for and managed several teams before retiring from professional baseball in 1931, at the age of forty-seven. However, he continued managing and sometimes playing for semi-pro teams in Atlantic City until 1942, and he later served as commissioner of the city's Little League

Dr Bank Robber's analysis:

As I said in the all-time team thread, he's my #1 shortstop ever

Although he was a soft-spoken, easy-going man who genuinely loved baseball, Lloyd was also a fierce competitor on the field and he was continually moving from one team to another to get a raise. "Wherever the money was, that's where I was," he once said.

Lloyd played second base in his first professional season with the Cuban X Giants in 1906, but was moved to shortstop when he joined the Philadelphia Giants the following year. After three seasons there, he went to the Chicago Leland Giants with several teammates and the Philadelphia team folded.

During the winters, Lloyd usually played in Cuba, where he was known as "El Cucharo" (the Shovel) because he often came up with pebbles and pieces of the infield dirt when he scooped up a grounder.

In 1910, his Cuban team played a 12-game exhibition series against the Detroit Tigers, led by Ty Cobb. Lloyd hit .500 to Cobb's .370.

Lloyd went to the Lincoln Giants in New York in 1911, and he moved back to Chicago, with the American Giants, in 1913. He stayed there through the 1917 season, then became player manager of the Brooklyn Royal Giants in 1918.

From that time on, Lloyd began to play first base more often than shortstop. He played for and managed several teams before retiring from professional baseball in 1931, at the age of forty-seven. However, he continued managing and sometimes playing for semi-pro teams in Atlantic City until 1942, and he later served as commissioner of the city's Little League

Dr Bank Robber's analysis:

As I said in the all-time team thread, he's my #1 shortstop ever

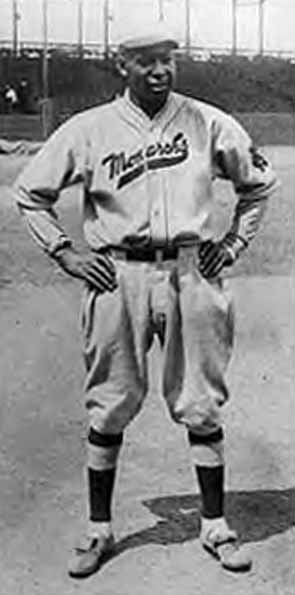

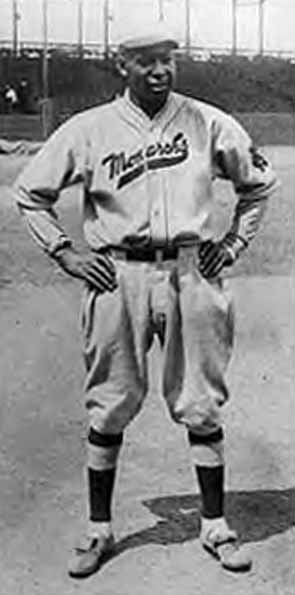

Bullet Joe Rogan

1889-1967

An outstanding pitcher with a tremendous fastball, a fine curve and good control, "Bullet" Rogan was a star for the Kansas City Monarchs for almost 20 years. The 5'9", 180-lb. right-hander was a smart pitcher who always kept the ball down. A durable workhorse, putting in an average of 30 games per year for a decade without ever being relieved, Bullet Joe's value to the team was inestimable. In addition to his pitching skills, he was a superb fielder and a dangerous hitter.

A versatile player, when not performing on the mound, Bullet played in the outfield to keep his big bat in the line-up. He showcased his stamina and versatility when he gained two victories in the 1924 World Series against the great Hilldale club, pitching three complete games and relieving in another, and batting .325 while playing in the outfield the other six games. That winter, in his only trip to Cuba, the hard worker continued his winning pace, recording a 9-4 worksheet.

The following year without Rogan on the mound in the World Series, the Monarchs lost to the same Hilldale club. In 1926, Bullet hit .331 and compiled a 12-4 record on the mound, which was tops for the first-half champion Monarchs, who lost a heartbreaking five-out-of-nine play-off to the second-half champion, Chicago American Giants. In a valiant effort to stave off defeat, Bullet Joe started both ends of a double-header on the last day of the play-off, but to no avail.

During his twilight years, Rogan served as manager of the Monarchs prior to his retirement in 1938.

1889-1967

An outstanding pitcher with a tremendous fastball, a fine curve and good control, "Bullet" Rogan was a star for the Kansas City Monarchs for almost 20 years. The 5'9", 180-lb. right-hander was a smart pitcher who always kept the ball down. A durable workhorse, putting in an average of 30 games per year for a decade without ever being relieved, Bullet Joe's value to the team was inestimable. In addition to his pitching skills, he was a superb fielder and a dangerous hitter.

A versatile player, when not performing on the mound, Bullet played in the outfield to keep his big bat in the line-up. He showcased his stamina and versatility when he gained two victories in the 1924 World Series against the great Hilldale club, pitching three complete games and relieving in another, and batting .325 while playing in the outfield the other six games. That winter, in his only trip to Cuba, the hard worker continued his winning pace, recording a 9-4 worksheet.

The following year without Rogan on the mound in the World Series, the Monarchs lost to the same Hilldale club. In 1926, Bullet hit .331 and compiled a 12-4 record on the mound, which was tops for the first-half champion Monarchs, who lost a heartbreaking five-out-of-nine play-off to the second-half champion, Chicago American Giants. In a valiant effort to stave off defeat, Bullet Joe started both ends of a double-header on the last day of the play-off, but to no avail.

During his twilight years, Rogan served as manager of the Monarchs prior to his retirement in 1938.

Leroy "Satchel" Paige was one who had a way with words and an even more magnificent way on the pitching mound. Paige was a long-time star in the Negro Leagues - there are estimates that he pitched for 33 years and won more than 2,000 games. Traveling all over the world to play baseball - by car, by bus, by train, some day also by horse and carriage - wherever there was a game the lanky hurler was there. His nick-name came from the fact that most of those years he lived out of his "satchel" or suitcase. Paige was proud of his nick-name and even wore it on his uniform.

A bone-thin 6'3" with size 12 flat feet, Paige billed himself as "The World's Greatest Pitcher." He claimed that his real secret of success stemmed from the fact that "even though I got old, my arm stayed 19." He was vigorously opposed to exercise. "I believe in training," he joked, "by rising up and down gently from the bench." Paige's rules for successful living were: 1 - Avoid fried meats which angry up the blood. 2 - If your stomach disputes you, lie down and pacify it with cool thoughts. 3 - Keep your juices flowing by jangling around gently as you move. 4 - Go very gently on the vices such as carrying on in society - the social ramble ain't restful. 5 - Avoid running at all times. 6 - Don't look back, something might be gaining on you.

Through all the long and difficult years in the Negro Leagues, Paige hungered for a shot at the majors. The Cleveland Indians needed extra pitching and their owner Bill Veeck was interested in Paige. As the story goes, Veeck wanted to test Paige's control before signing him to a contract. Allegedly Veeck placed a cigarette on the ground - a simulation of home plate. Paige took aim. Five fastballs were fired. All but one sailed directly over the cigarette. Paige got his contract!

On July 9, 1948, Leroy Robert Paige arrived on the major league baseball scene as a rookie pitcher for the Cleveland Indians. He gave his official age as "42???" to owner Bill Veeck. His exact age was always clouded in mystery and rarely did he answer questions about it. And when he did, he quipped: "Age is a question of mind over matter. If you don't mind, it doesn't matter But he definitely was the oldest rookie ever to play in the majors.

In 1948, Satchel won six games lost only one, compiled a fine 2.48 earned run average and helped pitch the Indians to the pennant and World Series victory that year. Three years later Veeck was re-united with Paige this time with the St. Louis Browns. Satchel passed the time away relaxing in his own personal rocking chair in the bullpen when he was not pitching. There were appearances in the All-Star games of 1952 and 1953. And then he was done - for a time.

In 1965, a year that would have made him 59 years old based on his "official birthday" (July 7, 1906 in Mobile, Alabama) - he pitched three shutout innings for the Kansas City Athletics to become the oldest man to pitch in a major league game. It was the last time he took the mound. In 1971, on what he called the proudest day of his life, Leroy "Satchel" Paige was elected to the National Baseball Hall of Fame. He was the first player ever elected from the Negro Leagues. Satchel Paige passed away on June 8, 1982 in Kansas City, Missouri. But stories of what he said and did have grown through the years, as the man has become both a myth and a legend. It is like the big fish story - the size of the fish caught grows bigger each time the teller of the tale speaks.

Nevertheless, Paige had the right stuff, hyperbole notwithstanding.

Satchel reportedly began his professional career in 1926 and was an immediate gate attraction with his dazzling variety of pitches, and words for every occasion. He played baseball year round, often pitching two games a day in two different cities in the Negro Leagues.

Joining the Pittsburgh Crawfords during the early 1930's, Satch was 32-7 and 31-4 in 1932 and 1933, respectively. But his time with the team was always interrupted by salary disputes. In those instances, Paige would go on barnstorming gigs for more money and compete against all levels of competition including top major league players.

He played in the Dominican Republic and then Mexico, where he developed a sore arm. In 1938, he signed with the Kansas City Monarchs and his arm was better than ever.

With the Monarchs, Paige had his complete pitching arsenal on display. He had a wide breaking curve ball, and his famous "hesitation pitch" that came out of a windup that looked like slow motion. He also had a "bee-ball," a "jump-ball," a "trouble-ball," a "long-ball" and other pitches without names that he made up as he went along.

Satchel pitched the Monarchs to four-straight Negro American League pennants (1939-42), accentuated by a clean sweep of the powerful Homestead Grays in the 1942 Negro League World Series. Satchel won three of the games in that series. In 1946, he helped pitch the Monarchs to their fifth pennant during his time with the team. Satchel also pitched in five East-West Black All-Star games.

In his time he graced, and dressed up, the rosters of the Birmingham Black Barons, the Baltimore Black Sox, the Cleveland Cubs, the Pittsburgh Crawfords, the Kansas City Monarchs, the New York Black Yankees, the Memphis Red Sox, and the Philadelphia Stars.

His career spanned five decades. In his time he was acknowledged as the greatest pitcher in the history of the Negro Leagues. It was a time when he had a string of 64 consecutive scoreless innings, and a stretch of 21 straight wins.

It was also a time when some saw Paige bring his outfielders in and have them sit behind the mound while he proceeded to strike out the side, and when some commented on how he intentionally walked the bases loaded so that he could pitch to Josh Gibson, black baseball's best hitter.

It was a time when there were the "out-of-thin-air-you-had-to-be-there" stories: Paige and his habit of striking out the first nine batters he faced in exhibition games; Paige and his firing twenty straight pitches across a chewing gum wrapper - a very mini-home plate; Paige throwing so hard that the ball disappeared before it reached the catcher's mitt.

The man they called "World's Greatest Pitcher" had a lot to say about his craft.

"I never threw an illegal pitch. The trouble is, once in a while I would toss one that ain't never been seen by this generation. Just take the ball and throw it where you want to. Throw strikes. Home plate don't move."

"They said I was the greatest pitcher they ever saw...I couldn't understand why they couldn't give me no justice."

Joe DiMaggio called him "the best and fastest pitcher I've ever faced."

And there were hundreds of others - major league and Negro League stars - that shared the Yankee Clipper's point of view.

A bone-thin 6'3" with size 12 flat feet, Paige billed himself as "The World's Greatest Pitcher." He claimed that his real secret of success stemmed from the fact that "even though I got old, my arm stayed 19." He was vigorously opposed to exercise. "I believe in training," he joked, "by rising up and down gently from the bench." Paige's rules for successful living were: 1 - Avoid fried meats which angry up the blood. 2 - If your stomach disputes you, lie down and pacify it with cool thoughts. 3 - Keep your juices flowing by jangling around gently as you move. 4 - Go very gently on the vices such as carrying on in society - the social ramble ain't restful. 5 - Avoid running at all times. 6 - Don't look back, something might be gaining on you.

Through all the long and difficult years in the Negro Leagues, Paige hungered for a shot at the majors. The Cleveland Indians needed extra pitching and their owner Bill Veeck was interested in Paige. As the story goes, Veeck wanted to test Paige's control before signing him to a contract. Allegedly Veeck placed a cigarette on the ground - a simulation of home plate. Paige took aim. Five fastballs were fired. All but one sailed directly over the cigarette. Paige got his contract!

On July 9, 1948, Leroy Robert Paige arrived on the major league baseball scene as a rookie pitcher for the Cleveland Indians. He gave his official age as "42???" to owner Bill Veeck. His exact age was always clouded in mystery and rarely did he answer questions about it. And when he did, he quipped: "Age is a question of mind over matter. If you don't mind, it doesn't matter But he definitely was the oldest rookie ever to play in the majors.

In 1948, Satchel won six games lost only one, compiled a fine 2.48 earned run average and helped pitch the Indians to the pennant and World Series victory that year. Three years later Veeck was re-united with Paige this time with the St. Louis Browns. Satchel passed the time away relaxing in his own personal rocking chair in the bullpen when he was not pitching. There were appearances in the All-Star games of 1952 and 1953. And then he was done - for a time.

In 1965, a year that would have made him 59 years old based on his "official birthday" (July 7, 1906 in Mobile, Alabama) - he pitched three shutout innings for the Kansas City Athletics to become the oldest man to pitch in a major league game. It was the last time he took the mound. In 1971, on what he called the proudest day of his life, Leroy "Satchel" Paige was elected to the National Baseball Hall of Fame. He was the first player ever elected from the Negro Leagues. Satchel Paige passed away on June 8, 1982 in Kansas City, Missouri. But stories of what he said and did have grown through the years, as the man has become both a myth and a legend. It is like the big fish story - the size of the fish caught grows bigger each time the teller of the tale speaks.

Nevertheless, Paige had the right stuff, hyperbole notwithstanding.

Satchel reportedly began his professional career in 1926 and was an immediate gate attraction with his dazzling variety of pitches, and words for every occasion. He played baseball year round, often pitching two games a day in two different cities in the Negro Leagues.

Joining the Pittsburgh Crawfords during the early 1930's, Satch was 32-7 and 31-4 in 1932 and 1933, respectively. But his time with the team was always interrupted by salary disputes. In those instances, Paige would go on barnstorming gigs for more money and compete against all levels of competition including top major league players.

He played in the Dominican Republic and then Mexico, where he developed a sore arm. In 1938, he signed with the Kansas City Monarchs and his arm was better than ever.

With the Monarchs, Paige had his complete pitching arsenal on display. He had a wide breaking curve ball, and his famous "hesitation pitch" that came out of a windup that looked like slow motion. He also had a "bee-ball," a "jump-ball," a "trouble-ball," a "long-ball" and other pitches without names that he made up as he went along.

Satchel pitched the Monarchs to four-straight Negro American League pennants (1939-42), accentuated by a clean sweep of the powerful Homestead Grays in the 1942 Negro League World Series. Satchel won three of the games in that series. In 1946, he helped pitch the Monarchs to their fifth pennant during his time with the team. Satchel also pitched in five East-West Black All-Star games.

In his time he graced, and dressed up, the rosters of the Birmingham Black Barons, the Baltimore Black Sox, the Cleveland Cubs, the Pittsburgh Crawfords, the Kansas City Monarchs, the New York Black Yankees, the Memphis Red Sox, and the Philadelphia Stars.

His career spanned five decades. In his time he was acknowledged as the greatest pitcher in the history of the Negro Leagues. It was a time when he had a string of 64 consecutive scoreless innings, and a stretch of 21 straight wins.

It was also a time when some saw Paige bring his outfielders in and have them sit behind the mound while he proceeded to strike out the side, and when some commented on how he intentionally walked the bases loaded so that he could pitch to Josh Gibson, black baseball's best hitter.

It was a time when there were the "out-of-thin-air-you-had-to-be-there" stories: Paige and his habit of striking out the first nine batters he faced in exhibition games; Paige and his firing twenty straight pitches across a chewing gum wrapper - a very mini-home plate; Paige throwing so hard that the ball disappeared before it reached the catcher's mitt.

The man they called "World's Greatest Pitcher" had a lot to say about his craft.

"I never threw an illegal pitch. The trouble is, once in a while I would toss one that ain't never been seen by this generation. Just take the ball and throw it where you want to. Throw strikes. Home plate don't move."

"They said I was the greatest pitcher they ever saw...I couldn't understand why they couldn't give me no justice."

Joe DiMaggio called him "the best and fastest pitcher I've ever faced."

And there were hundreds of others - major league and Negro League stars - that shared the Yankee Clipper's point of view.

New York Giants manager John McGraw said that lean, long-armed pitcher Jose Mendez was worth $50,000 - but in his day there was no market in organized baseball for a Cuban with coal-black skin. Mendez is generally regarded as one of the greatest Cuban ballplayers who did not play in the American major leagues.

Mendez was a smart pitcher who changed speeds well and had a rising fastball and sharp-breaking curve. Hall of Famer John Henry Lloyd said that he never saw any pitcher superior to Mendez. Arthur Hardy, another contemporary, said that Mendez threw harder than the legendary Smokey Joe Williams.

Mendez compiled a 15-6 record his first year in the Cuban Winter League. He came to America in 1908 and went 44-2 for the 1909 Cuban Stars (some games were played against semi-pro teams). He spent all of 1910 in Cuba, playing both summer and winter, going 18-2. By 1914 he had compiled a 62-17 record in Cuba, but he developed arm trouble and never again pitched there regularly.

Mendez played for the All-Nations of Kansas City from 1912 to 1916. The team was the most racially mixed of all time, carrying blacks, whites, Japanese, Hawaiians, American Indians, and Latin Americans on its roster. A barnstorming rather than a league club, the All-Nations played a high caliber of baseball, in 1916 going 3-1 against the powerful Indianapolis ABC's and splitting a series with the Chicago American Giants.

Mendez's greatest success came as a playing manager with the Kansas City Monarchs in 1920-26. Occasionally pitching and playing the infield, he led the Monarchs to three straight Negro National League pennants (1923-25). His pitching record was 20-4, with seven saves. In the 1924 Black World Series against Hilldale of the Eastern Colored League, Mendez was 2-0 with a 1.42 ERA in four games, including a shutout in the only game he started. In the 1925 BWS, also against Hilldale, he was 0-1.

Mendez was 8-7 in exhibition games against major league competition. He defeated Jack Coombs in 1908 and Hall of Famer Eddie Plank in 1909, and split two games with Christy Mathewson. (JM)

Mendez was a smart pitcher who changed speeds well and had a rising fastball and sharp-breaking curve. Hall of Famer John Henry Lloyd said that he never saw any pitcher superior to Mendez. Arthur Hardy, another contemporary, said that Mendez threw harder than the legendary Smokey Joe Williams.

Mendez compiled a 15-6 record his first year in the Cuban Winter League. He came to America in 1908 and went 44-2 for the 1909 Cuban Stars (some games were played against semi-pro teams). He spent all of 1910 in Cuba, playing both summer and winter, going 18-2. By 1914 he had compiled a 62-17 record in Cuba, but he developed arm trouble and never again pitched there regularly.

Mendez played for the All-Nations of Kansas City from 1912 to 1916. The team was the most racially mixed of all time, carrying blacks, whites, Japanese, Hawaiians, American Indians, and Latin Americans on its roster. A barnstorming rather than a league club, the All-Nations played a high caliber of baseball, in 1916 going 3-1 against the powerful Indianapolis ABC's and splitting a series with the Chicago American Giants.

Mendez's greatest success came as a playing manager with the Kansas City Monarchs in 1920-26. Occasionally pitching and playing the infield, he led the Monarchs to three straight Negro National League pennants (1923-25). His pitching record was 20-4, with seven saves. In the 1924 Black World Series against Hilldale of the Eastern Colored League, Mendez was 2-0 with a 1.42 ERA in four games, including a shutout in the only game he started. In the 1925 BWS, also against Hilldale, he was 0-1.

Mendez was 8-7 in exhibition games against major league competition. He defeated Jack Coombs in 1908 and Hall of Famer Eddie Plank in 1909, and split two games with Christy Mathewson. (JM)

A big, good natured lefty known as the "Cuban Strongman," Cristobal Torrienti was a walking ballclub. He is widely believed to have been the best right fielder in the Negro Laegues, blessed with sure hands, the speed to get under any drive, and a rifle-like arm. He was also an excellent 2nd baseman, amazingly good at 3rd for a southpaw, and a winning pitcher with a record of 15-5. To top it off, Torri was one of the finest hitters in any league.

Cristobal, a notorious "bad ball" hitter, had control to spray the ball to all fields, but best remembered for his power swing. Playing for the Chicago American Giants, he regularly hit line drives over 400-foot mark on the centerfield wall. Shortstop Bob Williams recalled that when the Giants visited Kansas City, Torri hit a line drive that cracked a clock 17 feet over the centerfield fence and "the hands just started goin' 'round and "round" In 1920, while Cristobal was in Cuba with the Havana Reds, the New York Giants came to town, bringing with them none other than Babe Ruth. In one game, Torrienti homered in his first two at bats, and came up for the third time with two men on base. Ruth, who'd been a top-notch starting pitcher in Boston, trotted in from right field and demanded to pitch to him. Torri promptly stroked a two-run double off Ruth and although Babe then struck out three in a row, he was back in the outfield next inning. Later, Torri slugged his third homer of the game. Back in the U.S., his clutch home run won the deciding game of the 1921 Negro Leagues World Series for the Chicago American Giants.

In a carreer that spanned 1913 to 1934, Torrienti earned a .339 average against black pitching, .311 against white Major Leaguers, and the respect of everyone who watched him play.

Cristobal, a notorious "bad ball" hitter, had control to spray the ball to all fields, but best remembered for his power swing. Playing for the Chicago American Giants, he regularly hit line drives over 400-foot mark on the centerfield wall. Shortstop Bob Williams recalled that when the Giants visited Kansas City, Torri hit a line drive that cracked a clock 17 feet over the centerfield fence and "the hands just started goin' 'round and "round" In 1920, while Cristobal was in Cuba with the Havana Reds, the New York Giants came to town, bringing with them none other than Babe Ruth. In one game, Torrienti homered in his first two at bats, and came up for the third time with two men on base. Ruth, who'd been a top-notch starting pitcher in Boston, trotted in from right field and demanded to pitch to him. Torri promptly stroked a two-run double off Ruth and although Babe then struck out three in a row, he was back in the outfield next inning. Later, Torri slugged his third homer of the game. Back in the U.S., his clutch home run won the deciding game of the 1921 Negro Leagues World Series for the Chicago American Giants.

In a carreer that spanned 1913 to 1934, Torrienti earned a .339 average against black pitching, .311 against white Major Leaguers, and the respect of everyone who watched him play.

"Home Run Johnson"

Dubbed "Home Run" for his power hitting during the turn-of-the-century dead-ball era, the righthanded-hitting Johnson was one of the pioneers of black baseball. His first team, the Page Fence Giants, which he formed with fellow pioneer Bud Fowler, played for a time in a white league in Michigan. Johnson moved on to play for what was regarded as the best black team of the early 1900s, the 1906 Philadelphia Giants, managed by Hall of Famer Rube Foster. Foster then took Johnson and five other players with him to form the Chicago American Giants of 1910, which Foster said was his best team ever. Playing in Cuba that winter, Johnson hit .412 against top competition that included the Detroit Tigers with Ty Cobb. In five years in the Cuban Winter League, he batted .319 in 156 games.

A star shortstop, Johnson moved to second base with the New York Lincoln Giants in 1912 to make room for future Hall of Fame SS John Henry Lloyd. Johnson finished his career as a playing manager in Buffalo, retiring at the age of fifty-eight.

Dubbed "Home Run" for his power hitting during the turn-of-the-century dead-ball era, the righthanded-hitting Johnson was one of the pioneers of black baseball. His first team, the Page Fence Giants, which he formed with fellow pioneer Bud Fowler, played for a time in a white league in Michigan. Johnson moved on to play for what was regarded as the best black team of the early 1900s, the 1906 Philadelphia Giants, managed by Hall of Famer Rube Foster. Foster then took Johnson and five other players with him to form the Chicago American Giants of 1910, which Foster said was his best team ever. Playing in Cuba that winter, Johnson hit .412 against top competition that included the Detroit Tigers with Ty Cobb. In five years in the Cuban Winter League, he batted .319 in 156 games.

A star shortstop, Johnson moved to second base with the New York Lincoln Giants in 1912 to make room for future Hall of Fame SS John Henry Lloyd. Johnson finished his career as a playing manager in Buffalo, retiring at the age of fifty-eight.

Martin Dihigo

1905-1971

Martin Dihigo, a 6'3" 210-lb righthanded Cuban, was one of the most versatile players of all time. His incredible skills gained him the unique honor of being elected to the Mexican, Cuban, and American Halls of Fame. Endowed with great speed and an exceptionally strong arm, Dihigo was a star performer at every position.

Dihigo began his American career in 1923 at the age of 18, playing first base with the touring Cuban Stars. He played in America from 1923 until 1936. After 1936 he played his summer ball in Mexico, except in 1945 when he was the player-manager of the New York Cubans. He reportedly continued to play in the Mexican Leagues until the 1950s, although his statistics are available only through 1947.

Statistics documenting Dihigo's American career exist for 1923-31, 1935-36, and 1945. In those 12 years, Dihigo hit over .300 six times, including .325 in 1926 with a league-leading 11 home runs in 40 games, and .333 in 1935 with a league-leading 9 home runs in 42 games. His overall American statistics show a .295 career batting average and a 6-1 record as a pitcher in 1931.

Dihigo was primarily a pitcher in Latin America, where he was known for his blazing fastball. His Mexican League totals show a lifetime .317 batting average in 10 seasons (1937-44, 1946-47), including a league-leading .387 in 1938. He was 119-57 as a pitcher in Mexico, going 18-2 with a 0.90 ERA in 1938 and 22-7 with a league-leading 2.53 ERA in 1942. He threw the first no-hitter in Mexican League history, and also had no-hitters in Venezuela and Puerto Rico.

Dihigo played for 24 seasons in Cuba (1922-29, 1931-46). The record of his Cuban career is somewhat fragmentary, but for the years which are documented (1922-29, 1931, 1935-46), he hit over .300 nine times, finishing with a lifetime .291 batting average. As a pitcher he was 93-48 in 1935-46.

Statistics exist for one year of play in the Dominican Republic (1937), when Dihigo hit .351.

Combining his Dominican, American, Cuban and Mexican statistics results in a lifetime .302 batting average with 130 home runs (11 seasons worth of home run totals are missing) and a 218-106 (.673) pitching mark. Dihigo often showed his versatility in Negro League competition by playing all nine positions in the course of a single game.

Known for his warm, friendly personality, Dihigo was a national hero in his native Cuba, where he served as Minister of Sport in his later years. He was elected posthumously to the American baseball Hall of Fame in 1977. In a poll conducted in the early 1980s among ex-Negro League players and other experts on black baseball, Dihigo gathered votes as best all-time outfielder and third baseman, and was voted to the first team all-time black all-star team as a second baseman.

1905-1971

Martin Dihigo, a 6'3" 210-lb righthanded Cuban, was one of the most versatile players of all time. His incredible skills gained him the unique honor of being elected to the Mexican, Cuban, and American Halls of Fame. Endowed with great speed and an exceptionally strong arm, Dihigo was a star performer at every position.

Dihigo began his American career in 1923 at the age of 18, playing first base with the touring Cuban Stars. He played in America from 1923 until 1936. After 1936 he played his summer ball in Mexico, except in 1945 when he was the player-manager of the New York Cubans. He reportedly continued to play in the Mexican Leagues until the 1950s, although his statistics are available only through 1947.

Statistics documenting Dihigo's American career exist for 1923-31, 1935-36, and 1945. In those 12 years, Dihigo hit over .300 six times, including .325 in 1926 with a league-leading 11 home runs in 40 games, and .333 in 1935 with a league-leading 9 home runs in 42 games. His overall American statistics show a .295 career batting average and a 6-1 record as a pitcher in 1931.

Dihigo was primarily a pitcher in Latin America, where he was known for his blazing fastball. His Mexican League totals show a lifetime .317 batting average in 10 seasons (1937-44, 1946-47), including a league-leading .387 in 1938. He was 119-57 as a pitcher in Mexico, going 18-2 with a 0.90 ERA in 1938 and 22-7 with a league-leading 2.53 ERA in 1942. He threw the first no-hitter in Mexican League history, and also had no-hitters in Venezuela and Puerto Rico.

Dihigo played for 24 seasons in Cuba (1922-29, 1931-46). The record of his Cuban career is somewhat fragmentary, but for the years which are documented (1922-29, 1931, 1935-46), he hit over .300 nine times, finishing with a lifetime .291 batting average. As a pitcher he was 93-48 in 1935-46.

Statistics exist for one year of play in the Dominican Republic (1937), when Dihigo hit .351.

Combining his Dominican, American, Cuban and Mexican statistics results in a lifetime .302 batting average with 130 home runs (11 seasons worth of home run totals are missing) and a 218-106 (.673) pitching mark. Dihigo often showed his versatility in Negro League competition by playing all nine positions in the course of a single game.

Known for his warm, friendly personality, Dihigo was a national hero in his native Cuba, where he served as Minister of Sport in his later years. He was elected posthumously to the American baseball Hall of Fame in 1977. In a poll conducted in the early 1980s among ex-Negro League players and other experts on black baseball, Dihigo gathered votes as best all-time outfielder and third baseman, and was voted to the first team all-time black all-star team as a second baseman.

Rube Foster

(1879-1930)

Rube Foster covered the entire spectrum of baseball and excelled at each phase of his participation. As a raw-talent rookie pitcher soon after the turn of the century, the big 6'4" Texan is credited with 51 victories in 1902, including a win over the great "Rube" Waddell, the game in which he received his nickname.

A smart pitcher who supplemented his normal repertoire of pitches with a highly effective screwball, the big right-hander's presence on a team usually was the determining factor in the championship. In 1903, pitching for the Cuban X-Giants, he won four games in the play-off victory over the Philadelphia Giants. The next year, after jumping to the Philly team, Rube won two games in the three-game play-off victory over his former teammates.

Rube's keen mind and ability to handle men naturally lent itself to achieving the next sequential step in his expanding perimeter of involvement. He became playing manager of the Leland Giants in 1907 and immediately this aggregation became the best team in black baseball.

In 1910 Rube assembled a team he considered to be the greatest baseball talent ever assembled. A dynasty was born that year, and the Chicago American Giants remained a dominant force until Foster's departure from baseball.

With the Giants, he molded players to fit his "racehorse" style of play. Good pitching, sound defense and an offense geared to the running game became the trademarks of his teams. All of his players were required to master the bunt and hit-and-run, so that the scrappy American Giants could always push across some runs and avoid prolonged team slumps. Only the 1916 Indianopolis ABC's were able to break his monoploly in the West as the American Giants won all other recorded championships from 1910 through 1922.

After finally establishing the black baseball team, Rube also organized the first black baseball league, the Negro National League, and oversaw it's develpment, assuring that it be maintained as a first-class entity.

Rube wore three hats, as a player, a manager and an executive. And they all set well on his head. However, it was for his contributions to baseball as a manger that he is best remembered. A stern disciplinarian, shrewed handler of men, developer of new talent,and ingenious innovator of baseball strategy, he instilled his philosophy and style of play in his players so that even after his mental health forced him to leave the game, his team and his league continued to flourish until after his death in 1930.

Black baseball's greatest manager, the man most responsible for black baseball's continued existence, and a man almost bigger than life itself, Rube Foster was voted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 1981.

Years played:

1902-1926

Positions played:

pitcher-manager-executive

Teams:

Chicago Union Giants, Cuban X-Giants, Philadelphia Giants, Leland Giants, Chicago American Giants

(1879-1930)

Rube Foster covered the entire spectrum of baseball and excelled at each phase of his participation. As a raw-talent rookie pitcher soon after the turn of the century, the big 6'4" Texan is credited with 51 victories in 1902, including a win over the great "Rube" Waddell, the game in which he received his nickname.

A smart pitcher who supplemented his normal repertoire of pitches with a highly effective screwball, the big right-hander's presence on a team usually was the determining factor in the championship. In 1903, pitching for the Cuban X-Giants, he won four games in the play-off victory over the Philadelphia Giants. The next year, after jumping to the Philly team, Rube won two games in the three-game play-off victory over his former teammates.

Rube's keen mind and ability to handle men naturally lent itself to achieving the next sequential step in his expanding perimeter of involvement. He became playing manager of the Leland Giants in 1907 and immediately this aggregation became the best team in black baseball.

In 1910 Rube assembled a team he considered to be the greatest baseball talent ever assembled. A dynasty was born that year, and the Chicago American Giants remained a dominant force until Foster's departure from baseball.

With the Giants, he molded players to fit his "racehorse" style of play. Good pitching, sound defense and an offense geared to the running game became the trademarks of his teams. All of his players were required to master the bunt and hit-and-run, so that the scrappy American Giants could always push across some runs and avoid prolonged team slumps. Only the 1916 Indianopolis ABC's were able to break his monoploly in the West as the American Giants won all other recorded championships from 1910 through 1922.

After finally establishing the black baseball team, Rube also organized the first black baseball league, the Negro National League, and oversaw it's develpment, assuring that it be maintained as a first-class entity.

Rube wore three hats, as a player, a manager and an executive. And they all set well on his head. However, it was for his contributions to baseball as a manger that he is best remembered. A stern disciplinarian, shrewed handler of men, developer of new talent,and ingenious innovator of baseball strategy, he instilled his philosophy and style of play in his players so that even after his mental health forced him to leave the game, his team and his league continued to flourish until after his death in 1930.

Black baseball's greatest manager, the man most responsible for black baseball's continued existence, and a man almost bigger than life itself, Rube Foster was voted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 1981.

Years played:

1902-1926

Positions played:

pitcher-manager-executive

Teams:

Chicago Union Giants, Cuban X-Giants, Philadelphia Giants, Leland Giants, Chicago American Giants

Biz Mackey

Considered by many the greatest catcher in Negro League history, Mackey was a master practitioner behind the plate. He possessed a powerful arm, and used the current standard "snap throw." He was strong enough to throw to second base from a sitting position, which he customarily did in between-inning warm-ups. He was a switch-hitter who batted for power and a high average.

Homestead Grays manager Cum Posey rated Mackey as his number-one all-time catcher: "Mackey was a tremendous hitter, a fierce competitor; although slow afoot he is the standout among catchers who have shown their wares in this nation." Roy Campanella was a 15-year-old with the Baltimore Elite Giants when Mackey taught him the fine points of catching. Campanella said, "I gathered quite a bit from Mackey, watching how he shifted his feet for an outside pitch, how he threw with a short, quick accurate throw without drawing back.

After two seasons with the San Antonio Giants, Mackey joined the Indianapolis ABC's and hit .352 in 1922 before being traded to the Hilldale team. He led Hilldale to their first title in 1923, batting .364. The next year he hit .325, helping Hilldale earn an invitation to the first Black World Series, against the Kansas City Monarchs. From 1922 through 1931, Mackey compiled a .327 average, with a high of .365 in 1930. In the first East-West all-star game, he was chosen over Hall of Fame teammates Josh Gibson and Oscar Charleston to bat cleanup.

Mackey's cherubic face and jolly nature never failed to delight fans and teammates. He completed his brilliant career as player-manager for the Newark Eagles. There he prepared Larry Doby, Don Newcombe, and Monte Irvin for the major leagues. Irvin called Mackey "the dean of teachers."

Considered by many the greatest catcher in Negro League history, Mackey was a master practitioner behind the plate. He possessed a powerful arm, and used the current standard "snap throw." He was strong enough to throw to second base from a sitting position, which he customarily did in between-inning warm-ups. He was a switch-hitter who batted for power and a high average.

Homestead Grays manager Cum Posey rated Mackey as his number-one all-time catcher: "Mackey was a tremendous hitter, a fierce competitor; although slow afoot he is the standout among catchers who have shown their wares in this nation." Roy Campanella was a 15-year-old with the Baltimore Elite Giants when Mackey taught him the fine points of catching. Campanella said, "I gathered quite a bit from Mackey, watching how he shifted his feet for an outside pitch, how he threw with a short, quick accurate throw without drawing back.

After two seasons with the San Antonio Giants, Mackey joined the Indianapolis ABC's and hit .352 in 1922 before being traded to the Hilldale team. He led Hilldale to their first title in 1923, batting .364. The next year he hit .325, helping Hilldale earn an invitation to the first Black World Series, against the Kansas City Monarchs. From 1922 through 1931, Mackey compiled a .327 average, with a high of .365 in 1930. In the first East-West all-star game, he was chosen over Hall of Fame teammates Josh Gibson and Oscar Charleston to bat cleanup.

Mackey's cherubic face and jolly nature never failed to delight fans and teammates. He completed his brilliant career as player-manager for the Newark Eagles. There he prepared Larry Doby, Don Newcombe, and Monte Irvin for the major leagues. Irvin called Mackey "the dean of teachers."

Donate

Any donations will be used to help pay for the site costs, and anything donated above will be donated to C-Dub's son on behalf of this community.